Navigating Complex PTSD through Art by Martina Franklin Poole

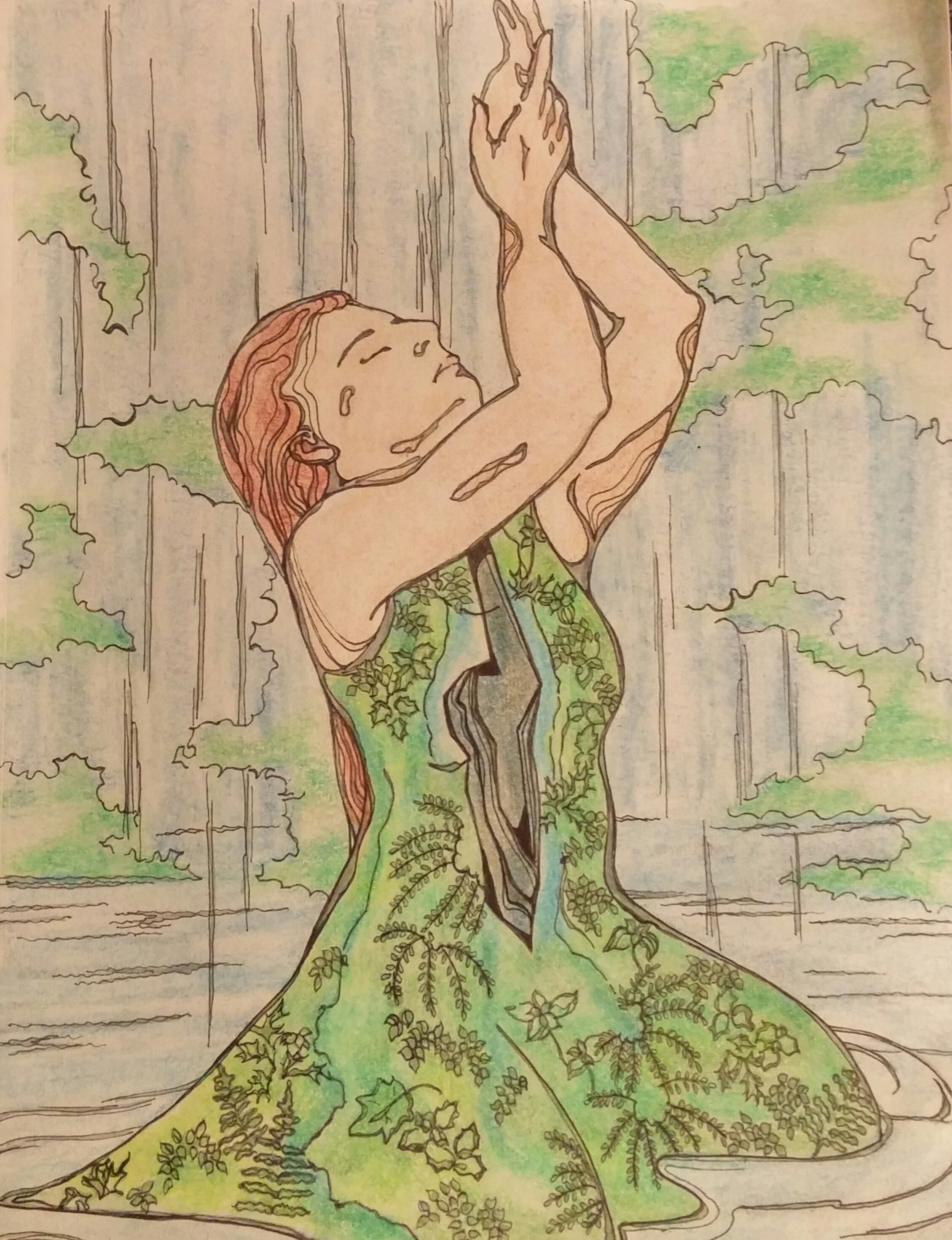

/In her book An Artist's Travel Log: An illustrated memoir of exploration in a wilderness obscured by trauma, Martina Franklin Poole reflects on how art helped her to navigate Complex PTSD.

“What am I supposed to do?” I asked her. She worked with women and children, victims of domestic violence according to the appointment reminder card in my hand.

“Some people like to hold an ice cube,” she said, more to her notes than to me. The previous week had yielded sage wisdom about feeling my feet, but without any explanation. I now had a diagnosis of PTSD and two coping tools. I thought of the noisy overwhelming public setting of my most recent embarrassing display of symptoms and wondered how I would ever find the mental clarity to look for an ice cube to ground myself.

It was the same year the news reported reuniting a kidnapped girl with her family. For 18 years she had been held prisoner and raped, even giving birth to two kids. For me it was 14 years and had one child, but I had signed a marriage certificate so it was hardly newsworthy. Yet there was that familiar feeling of detachment when seeing her story, watching it much the same way that I have always watched myself. I didn’t mention it to Ice Cube Lady. It didn’t really seem like she needed to know much about the actual violence, just that it existed. She didn’t seem to hear me and the sessions frustrated me. I decided I could manage on my own.

I was wrong. Fortunately, my next experience with therapy was different. After a brief intake interview I was contacted by a therapist who understood trauma. Marjorie was reassuring and infinitely patient. She had to do most of the talking for awhile, educating me about C-PTSD, practicing with me, and asking gentle questions. My vocabulary failed me. Perhaps my inability to identify more than three emotions helped her to discern that there was a long and painful childhood that I was escaping when I signed away my maiden name. She appealed to that invisible child with a handful of magic markers, and that is where my memoir begins telling the story, because that is when I started drawing again. I had difficulty telling her what I felt or what had happened to me, but I could hand her a drawing and respond to her. She would say “This makes me feel...” or “When I look at this I think of...” allowing me to agree and expand on the observation, to correct her and explain or to learn something about myself. Suddenly I had a language, and an ally.

Broken Windows

It helps me to view complex trauma as an injury instead of an illness or condition. My childhood development was interrupted by my early experiences. That is why my flashbacks and feelings can’t be communicated with facial expressions and words. They can come out in colors on my page, and the relief of that discovery has produced a portfolio. When Marjorie suggested parts of that portfolio could be published to help others, it was neat to think that something positive could come from so much agony. I started writing.

The drawings for the book were chosen and arranged in chronological order. The narratives came to me in a more random order and surprised me as they came together. Early on I had given in and decided to trust her, even though I could not figure out how our time together fit into any logical plan of care. Writing the memoir gave me an overview of just how much we had accomplished. It also gave me a deeper understanding of the nature of emotional health and well-being. Therapy wasn’t about making some mysterious list of goals and checking off my progress. Marjorie was teaching me to identify what I was feeling, to know it was appropriate to feel it, to be able to endure it and even, hopefully, appreciate it. My emotions are not the source of my suffering. They are a temporary reaction to the suffering. Therapy was slowly teaching me to respond as an emotional being as I watched Marjorie allowing herself to respond to me.

Damage Undefiled

As a child I was carefully instructed that I was different and that others should never be expected to understand me. My body was somehow deformed or broken and couldn’t do what other kids did. I was only loved because they were my family and they “had to” love me. The words were reinforced with actions. It feels almost as though I was being specifically trained to have symptoms of C-PTSD. It’s not easy as an adult to replace childhood lessons like these. We need all the help and support that we can find. If my words or drawings help one other person to feel less alone or find words in therapy, then my book is a success.

An Artist’s Travel Log: an illustrated memoir of exploration in a wilderness obscured by trauma is available on Amazon and can be accessed through the OOTS booklist.

A little about me: I live in the Pacific Northwest with my teenage daughter, two dogs and a cat. I work as a billing specialist for a medical group with seven clinics and a home health team. Our department supports both medical staff and mental health staff as we move toward providing complete patient care. I rely on my faith, my chosen community, my role as a mom, my creativity, my garden and my therapist to get me through each week.

Website: martinafranklinpoole.com Twitter: MartinaFPoole Instagram: martinafranklinpoole