How Victims become Perpetrators: Passing War Trauma on to Your Own Children by Martin Miller

/In this compelling article psychologist Martin Miller, son of well-known child advocate, psychologist and author Alice Miller, discusses the abuse he suffered as a child due to his parents’ unrecognized and unresolved war trauma.

1. Introduction

We are still suffering in this world as a result of past wars and new ones are coming. The psychological consequences continue to be hidden and taboo. The survivors of the Holocaust survived in the worst conditions and no one managed to forget the terrible experiences and return to a normal life after surviving. In various ways the victims of the Holocaust have mostly passed on their traumatic experiences to the next generation. If one deals critically with these behaviors as a person affected by this generation, then one encounters great resistance and is violently attacked. When I published my book about my mother [The True Drama of the Gifted Child], the famous childhood researcher Alice Miller, I received the following criticism from the Jewish community: "Martin, You should never have published this book. Because everything you have experienced is nothing compared to the suffering your mother experienced in the war. You have never had the right to emphasize your suffering, because it is directly an arrogant presumption to articulate your suffering so clearly, because there is no suffering." I was very surprised and hurt by this criticism because every person who has had a traumatic experience has a right to articulate their bad experiences and deserves understanding from other people. Many people suffer from traumatic experiences and are even ashamed to tell their story openly because they are afraid of not being taken seriously.

In the following article, I will describe my experiences with the transgenerational inheritance of war trauma to encourage other people to acknowledge and resolve their traumas more confidently.

2. Experiencing trauma and its devastating mental consequences

Unfortunately, classical psychotherapy still has a lot of work to do to finally be able to treat patients with traumatic experiences professionally. Someone who suffers ongoing relational trauma is often unable to integrate this overwhelming emotional stress which is different from physical injury in which the body usually has the ability to heal. In the event of a psychological trauma, we do not have these self-healing powers. Until recently, it was still believed in good faith that the healing of trauma depends on the mental resilience of the person. It was thought it would also be possible for people to be able to overcome and process trauma through self-healing. As is often said, ‘time heals all wounds’.

Today, we know otherwise. There are events that trigger deep trauma and these hurtful experiences significantly affect someone's life until the trauma has been resolved with outside help. While today we have the necessary knowledge on how to treat trauma therapeutically, acceptance in society still leaves a lot to be desired.

How does a survivor usually deal with their traumatic experience? The victim tries with all their might to manage their trauma. The primary objective of coping is to wipe away the traumatic experience at all costs. In so doing, survivors use defense mechanisms that use up a lot of energy, are very strenuous and stressful. The survivor subordinates their whole life to this goal and due to fear avoids any repetition or reliving of the trauma at all costs. Either they get sick and retreat and/or they develop mental disorders, depression, psychosis or even personality disorders.

In other cases, however, it is not uncommon for the victim to identify with the perpetrator. The traumatic experience of being and becoming a victim gets completely split off and the victim identifies with the perpetrator and projects victim trauma onto others. People with a war-trauma transfer their experience through projection to their children in a variety of forms, passing on their unprocessed traumatization to the next generation.

3. My own traumatic experience: My persecution as a Jew in the Aryan part of Warsaw during the war.

My mother [Alice Miller] was born and raised in the small Polish town of Piotrkow, south of Lodz. She came from a large, extended Orthodox Jewish family and they lived in a large house in a desirable area. When the Germans occupied Poland in 1939, they built the first ghetto in Poland in Piotrkow. My mother's whole family had to give up the family home and move to the ghetto. At the age of 16, my mother together with her older boyfriend founded an underground high school for the Jewish students. She also joined the underground movement right away and got herself false identity papers. From then on she completely gave up her Jewish identity and became Alice Rostovska, a Polish woman. With these false papers, she moved to Warsaw and made her money as a private teacher of well-heeled Poles. Just two days before everyone was deported from the Piotrkow ghetto, she managed to free her mother and sister with false papers and they fled to Warsaw. She had to leave her father in the ghetto because both his appearance and his speech - as an Orthodox Jew he understood only Yiddish and spoke no Polish - he would have had no chance of survival outside the ghetto. She hid her mother and sister in a Catholic monastery in Warsaw. Her sister survived by being renamed into the Catholic faith, and her mother survived in the countryside. Alice went to Warsaw with her boyfriend at the time, with whom she had run the high school in the ghetto. There, they parted ways for security reasons. She went underground and taught Polish students and lived in a Polish school in the Aryan part of Warsaw.

.…Stefan saved his own life by revealing the names of his girlfriend (my mother) and of all his friends in the underground.

Then her boyfriend Stefan was suddenly blackmailed in the Aryan part of Warsaw by a Polish blackmailer allied with the Gestapo. In a long essay decades later, Stefan describes his experiences in the war and names his blackmailer. The blackmailer was called Andreas Miller, just like my father. Stefan's account of how he gave up all his values to survive is very impressive. He adapted more and more to the blackmailer and began to build a friendly relationship with him. But the blackmailer became more and more threatening to him, so Stefan saved his own life by revealing the names of his girlfriend (my mother) and of all his friends in the underground. Andreas left him alone and began blackmailing my mother instead. My mother survived by cooperating with Andreas and they became lovers. My mother once betrayed herself to me when she told me the Polish blackmailer had had the same name as my father. Today I know that the blackmailer actually was my father. Together with her sister, my mother fled over the Vistula River to the Russian side during the Warsaw Uprising, leaving Andreas Miller behind.

After the War, Poland immediately became communist; their party was full of ardent supporters of Stalin. Stalin persecuted all Jews after the war and so the remaining Jews in Poland were again persecuted and killed. My mother first studied in Krakow, but then moved to Lodz, where Andreas Miller was already enrolled as a student. He met my mother there and they became a couple again. In that way, through “love”, my father Andreas Miller turned from persecuting blackmailer into my mother’s savior. In 1946 he organized a scholarship for himself and my mother at the University of Basel in Switzerland. In late 1946 my parents left Poland together forever and moved to Switzerland. They studied in Basel and graduated with doctorates. Both studied Philosophy. My father specialized as a sociologist, my mother became a psychologist. That's where they got married and I was born there in 1950.

From the beginning, as a Jew I was a thorn in the side of my father because if the mother is Jewish, then the child is automatically as well. For him, it was unconscionable, as a staunch anti-Semite and former Nazi, to have fathered a Jewish son and so he forced my mother to hand me over to a stranger after giving birth, hoping I would die. Thank God, I was saved by my aunt, who had also immigrated to Switzerland from Poland as a refugee with her daughter and husband. My mother's aunt cared for me, and her daughter Irenka, my cousin, also gave me the optimal care I needed as a baby for the first seven months of my life. If I hadn't had this bonding experience, I would almost certainly have died or at best my life would have taken a catastrophic course. My mother brought me back to her after seven months and I was back in the “hellhole of war”.

At first, I developed a bad separation trauma. Irenka, my cousin who cared for me as an infant, told me that while my parents visited my aunt for the first seven months of my life, they didn't care at all about or for me. I developed a strong bond with Irenka and her mother and separation from them also meant trauma for me because my own mother was a stranger to me. In fact, she remained a stranger to me until her death.

When I started speaking, my mother wanted to teach me Polish, because that was my real mother tongue. My father prevented me from learning Polish. Later, I heard my parents’ excuses: "We wanted to make you a good Swiss person. And by the way, many people thought it would be bad for your intellectual development if you learned two languages."

Later, my traumatization became more and more intensified. My parents always spoke Polish to each other in my presence and I could never understand what they were talking about. I felt totally excluded. When I found out my parents’ true war story decades later, I understood. Orthodox Jews never spoke Polish in Poland at the time but spoke Yiddish. In that way they were excluded from society. I spoke Swiss German, a dialect that sounds very similar to Yiddish. In a similar way I was excluded by my parents when they spoke Polish.

Further, I was humiliated, despised and degraded by my father at every opportunity. He also beat me regularly, fiercely and mostly for no reason, just out of the blue. Such experiences are traumatic because as a child you don't understand at all why your own father turns on you so brutally and violently and it always comes unexpectedly. That’s the result of being helplessly at the mercy of such a person. You then constantly think about what you could do to avoid this thunderstorm of violence, but it is pointless. My mother watched terrified and never protected me from this monster. She – the famous author and childhood researcher Alice Miller - later labeled such parental behavior as a crime.

Today I know that I became the Jew persecuted by the blackmailer Andreas Miller. My mother sat and stared in silence with anxiety-filled eyes and never protected me. Today I know that I innocently ended up in the same situation as my mother in the Second World War. My role in the family enabled my mother to survive the war again, and the terrible relationship of my parents was projected onto me. My mother was also very afraid to introduce me to the culture of Judaism. I had to become a Catholic.

Only today am I able to know and understand my story exactly. I am absolutely appalled at how I was deceived by my parents in every way. They told complete lies and never talked about their experiences during the war. I became the victim of a transgenerational war trauma, transferred to me by my parents.

4. Can victims of such a traumatic experience process the trauma suffered?

In current psychotherapy, there are various methods of processing trauma. I have had the experience personally and in my many years of practice, that trauma can only be processed if the trauma experienced is transformed into a narrative that is integrated as part of your life story, albeit a difficult part of it.

At first, it seems absurd to talk about narrative because in the context of social sciences a narrative is a meaningful story that influences the way you see the world around you. Narrative conveys values and emotions. In this sense, narratives are not just any old stories, but established tales, with legitimacy within a group or society.

On the other hand, experiencing trauma is never meaningful and always perverse and reprehensible. Even so, the narrative helps us process our traumatic experience. For in narrative I can clearly justify my subjective experience as my very own experience. This makes it possible for me to cope with my hurtful, senseless experience. I can talk about it without fear and, above all, I no longer have to suppress the trauma. I no longer have to suffer two-fold - under both the stress of the original trauma and the stress of the wide-ranging psychological side-effects which greatly restrict simply living my life. When you’re traumatized, your life becomes a living hell. I no longer have to identify with the perpetrator and I no longer traumatise other people which can happen as a result of splitting off from your own trauma.

Even though I've processed my trauma, I will never be a cheerful person again. I am reminded of my trauma again and again by continuing life experiences, but I know that I can deal with it by processing it. Anyone who has experienced trauma has a scar that keeps making itself felt. Thanks to my knowledge and experience in therapy, I know how to deal constructively with the unpleasant memories. My traumatic experiences become the past and no longer dominate the present.

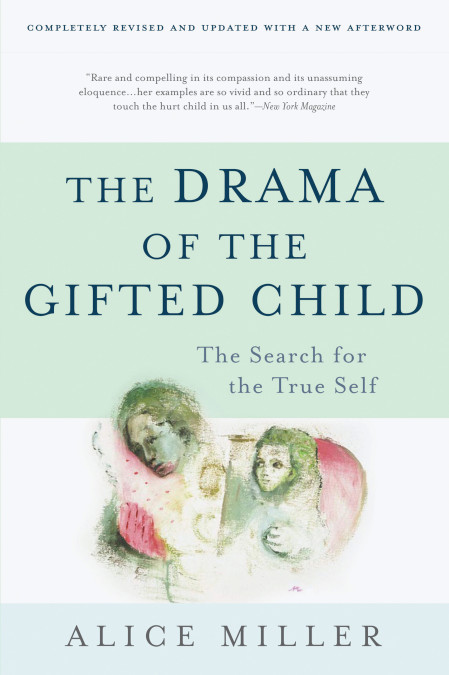

Martin Miller’s book The True “Drama of the Gifted Child” and his mother’s book The Drama of the Gifted Child are available from Amazon.