Pete Walker’s Top 10 Practices for Navigating Complex PTSD - Part 2

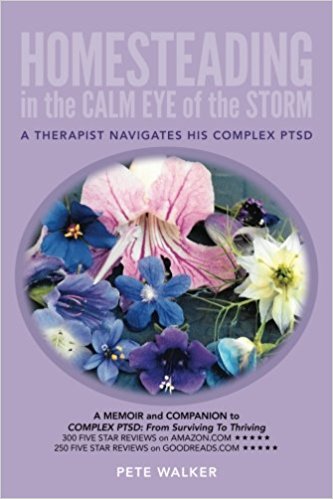

/Pete Walker, author of Homesteading in the Eye of the Storm writes about his top ten practices for navigating Complex PTSD.

6. Meditation: There’s No Boogeyman in My Inner Closet

At my first ten day meditation retreat I was cooped up inside myself without distraction or diversion for ten straight days. Damn! That was intense. But it left me knowing – at least most of the time – that there was nothing wrong with me – nothing inside me that I had to flee, hate or be ashamed of. Ten years later, during my second ten day retreat, I anchored that understanding by practicing… 24/7… this guidance from Galway Kinnell:

What Is

Is

Is what I want

Only that

But that

From that time on, I learned to use Vipassana to rescue myself from thousands of flashbacks. For me, the quickest way back to calmness is to fully feel what I am most reluctant to feel. Now when I get triggered into a flashback, my dominant urge is to find a safe place to meditatively feel into the sensations and emotions of my upset as fully as I can. Within twenty minutes, the flashback almost invariably resolves and I am once again at peace with myself. Stephen Levine’s Who Dies and Jack Kornfield’s A Path with Heart are two great books that teach this invaluable skill.

7. Getting and Giving Individual & Group Therapy

I needed to be reassured by many good-hearted authors before I could face the fear of seeking help from a stranger. I was a client of various therapists off and on for twenty-five years. Without that experience, my effectiveness as a therapist would have been quite limited. Receiving and providing therapy have been the yin and the yang of my ongoing training…training that informs me about what can and cannot be accomplished in psychotherapy.

Individual Therapy

Numerous helpful short-term therapies, and co-counseling with my friends Randi and Nancy, made me want long-term, depth-work psychotherapy. As described earlier, my first foray with Kleinian Dr. L was awful. To avoid repeating this, I had test- sessions with seven highly touted therapists. In one interview-session after another, each renowned therapist tried to distract me from venting pain. It was so hard to believe. Each paid lip service to welcoming grief, but when my feelings surfaced, they apparently could not go where they had not been.

After the sixth, I despaired about finding a therapist who would welcome my emotional pain. I reread some of the therapist-writers who insisted that shame about emotional pain could only be worked through with a supportive witness. I scheduled a seventh appointment and mercifully I finally found Gina. Hundreds of sessions with her over five years brought me profound relational healing. My toxic shame lost its life support system. My toxic critic became an endangered species, and at times I almost disliked automatically shooting it on sight. ~

Through my experiences as a client, I discovered in the laboratory of my own psyche what actually helps. What especially struck me was that all my helpful therapists reparented me to some degree. As an extra bonus, many also served as role models on how to do therapy. Thank you, thank you, thank you Derek, Bob, Randi, Nancy, Gina and Sara for your psyche-renovating help – for helping me truly befriend myself.

As a therapist I noticed that most clients suffer shame and self-hate over similar issues. I heard endless self-flagellation over the same minor flaws, “bad” feelings, taboo fantasies, and small potato mistakes. So many humiliated confessions about such common harmless human imperfections! How tragic that perfectionism shames us into hiding the same innocuous “shady secrets.” As I consistently felt no judgment about my clients “flaws”, the glacier of my own self-judgment gradually melted into a snowball.

I have facilitated more than thirty thousand therapy sessions, and frequently experienced healing in the manner I describe in Appendix 2. How blessed I am that I have had so many clients who I easily care about and respect. A great turning point occurred decades ago when I learned to quickly nudge bona fide narcissists out of my office. Dyed-in-the-wool narcissists do not seek transformation. They only want adoring listeners whom they can control and suck dry. Too many become even more entitled from the process of therapy – believing that everyone owes them fifty minutes of uninterrupted listening.

Group Therapy

What a boon that so many of my university courses featured group therapy. Sydney University was way ahead of its time. Antioch was the most profound. At Antioch, Will Schutz taught me to do anger work in a way where no one hurt themselves or anyone else. I often left group feeling purified by the cleansing flame of therapeutic angering. What a privilege to pass this gift onto others!

My disappointment in the poor quality of JFK groups was tempered by the sheer quantity of experience. JFK shortcomings matched the old saying: “Good and bad experiences are like the right and left hand. The wise person uses both to his/her benefit.” From JFK, I learned to avoid the mistakes that commonly spoil group therapy. I guarded my groups from being hijacked by narcissists. I immediately stopped shaming and scapegoating behaviors, and divvied up the time so that all members shared equally.

I was also a member of many support groups. Really liking and being liked by others with similar vulnerabilities helped pry perfectionism off my self-esteem. My men’s support group was the heart of my created family for fifteen years. My imperfections were met with nothing but kindness. I cannot thank you guys too much for your healing support!

This all culminated with an ACA/Codependency/CPTSD support group that I lead for twenty-five years. It was by far my most potent experience of the hub of mutual relational healing [see Appendix 2]. Members often grieved together about the pain caused by their selfish parents. They cried together and they angered together. They healthily blamed their parents for forcing them to fawn and abandon themselves – for making them easy pickings for exploitative narcissists. The group’s mutual empathy shrunk their inner critics and bred self-kindness. Most members went on to find at least one other island of human safety in the world outside of the group. I was not a “working member” of the group, but often felt vicariously comforted and healed by group commiseration. I treasure everyone who “graduated” from this group. I wish I could name them for posterity, but of course confidentiality prohibits.

Sometimes when I flash back into alienation, I remember all the groups that gave me their esteem when “mortified” was my middle name. Accordingly, I often advise survivors to join a support group – on line or in vivo. Many respondents to my writings have testified to the helpfulness of such connections.

8. Self-Reparenting: Finding an Inner Mom and Dad

I am forever indebted to John Bradshaw for exposing the epidemic of traumatizing parents. Such parents create children who grow up developmentally arrested in myriad ways. Bradshaw gave us many reparenting tools to meet the unmet needs of survivors of such abandonment.

Over time, I also discovered tools of my own which I used to reparent myself and my clients. I taught many clients through modeling to take over the job of ongoingly mothering and fathering themselves.

In my own recovery, my critic upped its scoffing to a new level when I first heard about inner child work. I had to bypass my inner child at first and just work with the concept of healing my developmental arrests. Thankfully I eventually whittled down my critic and built a profoundly therapeutic relationship with my developmentally arrested, infant, toddler, preschooler, primary schooler and adolescent.

Through continually evolving my ability to nurture, love and protect myself and my various child selves, I customarily feel a sense of safety and of belonging in the world. [Guidelines for this process can be found in Chapters 8 & 9 and Appendix C of The Tao of Fully Feeling.]

9. The Created Family: Healing the Loss of Tribe

The love of my grandmothers and my sisters, Pat, Diane and Sharon, helped keep my heart alive despite all the parental and clerical abuse. Growing up in New York City as a baby boomer gave me access to a wealth of kids on the street, and I had many safe enough friends, although I also had to learn to steer clear of numerous bullies. Moving to Dover, New Hampshire as an adolescent opened the door to more supportive friendships, especially the one with my lifetime friend, Bruce McAdams. Even the army brought me many good enough friends. I also met many kind and respectful people during my travels. All this gradually restored my trust in human nature.

Communal living greatly bolstered this trust. Fifteen years with kind roommates soothed me with relational healing. How lucky I was to come of age during the hippie times. I was especially fortunate to live for a decade in Australia while the Hippie Zeitgeist of loving cooperation still endured. During this time, many layers of my deep CPTSD fear of people dissolved. Empirical proof accumulated that destructive narcissists like my parents were a small part of the population. I bet they are less than ten percent. Sadly, communal living ended for me thirty years ago. Happily, it was gradually replaced with a looser sense of tribe. I experience my current clan as concentric circles of intimacy. My inner most circle is my wife, son and a handful of close friends with whom I can easily be my whole self.

The next circle is a group of old friends I see infrequently but immediately feel close to when I do. Outside that circle is less intimate friends and family members with whom I am usually comfortable via many years of safe interactions. A final superficial but warm circle is safe-enough acquaintances from my neighborhood, my son’s school and my membership in community organizations. Intermingling with various arcs of this circle are the many people I no longer see but still hold dear in my heart.

When I am actively engaged in flashback management, I sometimes visualize a human mandala of all these circles as Step 10 [Seek Support].

10. Gratitude: A Realistic Approach

Yesterday I laughed aloud at a cartoon in The New Yorker. Moses, with the Ten Commandments in hand, was looking up toward God and calling out: “Now, how about some affirmations to balance out all this negativity.”

Twenty years ago I began my end-of-the-day gratitude practice. Upon laying down each night I spend five minutes using my breath to relax me. To better appreciate the day, I then recall ten things for which I am grateful. Even on gloomy days, I usually find ten worthwhile things. Usually it’s simple stuff: an especially sweet pear, something funny that Sara or Jaden said, a new flower that bloomed in my garden, a cloud with a striking shape, a sense of being healthy when I stretched, a dull radio background sound that suddenly morphed into a tune that begged for my accompaniment.

Gratitude is a thought-correction practice that gradually eroded the negative noticing of my toxic critic. Now, I refuse to let all-or-none thinking throw out the baby of daily niceties with the bathwater of normal disappointments.

Here is how I keep this practice fresh. I accept that I do not always feel gratitude while I am expressing it. As I argue in my first book, our feelings are rarely a matter of choice. But gratitude is more than a feeling. Gratitude is also a health-inducing perspective that with enough practice grows into a belief. So while I may not feel grateful for my wife while we are struggling about something, I almost always know she is a blessing in my life. And although life can bring unpredictable difficulties, bounteous wonder usually tips the scale and makes me grateful to be alive.

Sometimes I have difficulty with the homily “Stop and smell the roses.” In my old all-or-none days, I was bitter when their perfume did not rescue me from feeling bad. Nowadays though, I still love flowers even when they do not move me. And, I still dislike it when someone tries to fast-fix my pain by pointing them out.

On a larger scale this is true of gratitude and love in general. At times Monet’s paintings, my favorite songs or even kindnesses from others do not impact me. Yet, in a wider spiritual sense, I am always grateful for these gifts because I know from experience that sooner or later I will fully appreciate them again. So, I accept the cyclical nature of feeling love and gratitude, knowing that I will repeatedly be moved by the bounty of the world. Color, flowers, nature, food, panoramas, music, movies, kindnesses, pets, and so on, will inevitably move me again even when they momentarily leave me cold.

Back in the late twentieth century, the practice of Be-Here-Now [based eponymously on Ram Das’s book] was considered to be the height of wisdom in many spiritual circles. Invoking “Be Here Now!” was supposed to make you instantly return to feeling grateful and loving. I soon came to hate this phrase however, because I hated myself for not being able to do it on command. Even worse, be-here-now was often callously shoved in the face of anyone who was having a hard time.

Once in a JFK group, a student sporting an ascended master persona told a woman distraught about the recent demise of her twenty year marriage: “If you weren’t so attached to the past, you wouldn’t be so upset. Try to Be Here Now!” Over time, “be-here-now” morphed into “just be grateful!” which in turn acquired a flight-into-light subtext: “If you just get your mundane head out of your unspiritual ass, and flip the gratitude switch, your pain will instantly vanish.” Unfortunately I still regularly see this shaming corrective use of gratitude…especially in Marin County, the nesting place of the world’s largest population of flight-into-lighters.

For my own use, I have ironically converted be-here-now from an elixir to a reminder: Be here now, Pete. Drop down into that pain and feel your way through it. Usually this soon restores me into authentically being here now.

Don’t Sweat the Small Stuff is a more modern version of be-here-now. It’s a great book title and idea by itself, but it’s instantly ruined by the book’s small print subtitle: And it’s All Small Stuff. Hopefully at this point I don’t need to explain the nonsense in that.

An anonymous reader sent me this poem.

In which I count to ten, grateful that:

Spider webs catch sunlight and moonbeams.

Long-lost lovers sometimes reappear.

Women make an art out of friendship.

Wisdom wanders the world planting stories.

People transform pain into blues.

Weather changes.

Sloths are not extinct.

Turkey contains serotonin.

Frequently accidents are not as bad as they might be.

Love abides.

Pete Walker is a relational therapist and author in California who both suffers from and treats Complex PTSD. As many in the Out of the Storm community will attest, his books resonate deeply with those of us who endured trauma in childhood. At the same time as he shares his lived experience with us in a way we can understand, he offers us personal and therapeutic insights into navigating Complex PTSD. Pete's web site.